Green Heron

General Description

A solitary and secretive bird, the Green Heron is stocky, dark colored, and small for a heron. The adult Green Heron has a dark rufous neck, gray belly, and dark, iridescent, greenish-blue back. The upper mandible of the bill is dark, and the legs are bright orange. The juvenile has a brown-and-white streaked neck, slight crest on its dark head, and prominently light-tipped wing coverts. Yellow spectacle-shaped markings surround the eye and extend to the bridge of the bill. These markings are present, but less pronounced, in the adult.

Habitat

Green Herons inhabit small, freshwater wetlands, ponds, and stream-sides with thick vegetation at their margins. In winter, they frequent coastal areas and mangrove swamps.

Behavior

The solitary Green Heron usually forages from a perch, where it stands with its body lowered and stretched out horizontally, ready to thrust its bill at unsuspecting prey. One of the few birds known to use tools, the Green Heron will attract prey with bait (feathers, small sticks, or berries) that it drops into the water. When out in the open, it commonly flicks its tail nervously and raises and lowers its crest. Another characteristic behavior of the Green Heron, which may help with identification, is its tendency to fly away from a disturbance giving a squawk and defecating in a white stream behind itself. (Other small herons defecate forward.) When alarmed, the Green Heron may adopt the classic bittern stance, with head held vertical, looking across the base of its bill. The Green Heron commonly calls in flight--a sharp skeow or kyow sound.

Diet

Fish are the primary food of this opportunistic feeder. Crayfish and other crustaceans are also a source of food, as are aquatic insects, frogs, grasshoppers, snakes, and rodents.

Nesting

Green Herons typically nest in trees near the water. Males stake out territories and call to attract females. Sometimes pairs form in migration, and the pair will select the site together. Unlike most herons, the Green Heron does not typically nest in large colonies. The male starts the nest, bringing long, thin sticks to the female who finishes the nest. Both parents incubate the 3 to 5 eggs for about 19 to 21 days. Once the young hatch, both parents feed them by regurgitating food. Both help brood the young for about three weeks. At about 16 to 17 days, the young climb about near the nest, and they first start to fly at 21 to 23 days. The parents continue to feed the young for a few more weeks until they fledge after about 30 to 35 days.

Migration Status

Most of the Green Herons that breed in Washington, like other Green Herons in all but the southernmost US, withdraw to the south in winter, leaving in late August or early September. Small numbers of wintering birds remain in the region. Post-breeding wandering is not uncommon.

Conservation Status

The nationwide population of Green Herons appears stable, but estimating numbers is difficult due to their secretive nature. They were first reported in Washington in 1939. The first nests in this state were discovered in 1960, and their range appears to be expanding in this region. Numbers in eastern Washington may be increasing. Threats to the population include predator control at fish hatcheries and disturbance during the nesting season. Pesticides appear to be less of a threat for Green Herons than for other heron species. As is the case with most wetland species, habitat loss and degradation are the primary concerns to the population. For Green Herons, protection of small wetlands is especially important.

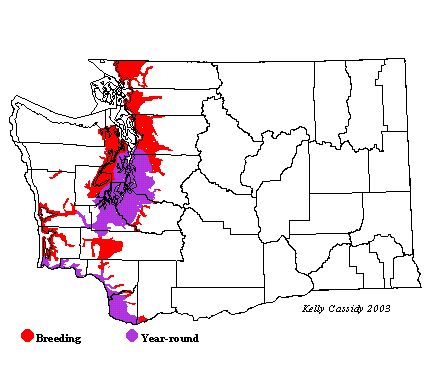

When and Where to Find in Washington

Green Herons are uncommon to fairly common, but local, at low elevations in western Washington from April through October. The birds that winter in Washington are seen rarely, from November to March, in the southwestern part of the state, up to the southern tip of Puget Sound, and along the coast. They are rare in eastern Washington.

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | R | R | R | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | R | R |

| Puget Trough | R | R | R | U | F | F | F | F | F | U | R | R |

| North Cascades | R | R | R | R | R | R | ||||||

| West Cascades | R | R | R | U | U | U | U | U | U | R | R | R |

| East Cascades | ||||||||||||

| Okanogan | ||||||||||||

| Canadian Rockies | ||||||||||||

| Blue Mountains | ||||||||||||

| Columbia Plateau |

Washington Range Map

North American Range Map